Loading and the growing athlete

Hey team,

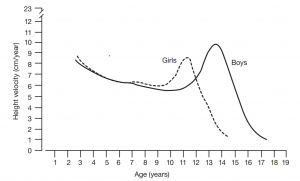

With the opportunities to be involved in organised sport at a record high for our growing children, there are also a number of young people who are suffering from pain as a result of doing their sport. In the sporting context the term ‘loading’ refers to the amount of physiological stress placed on the body by activity. The amount of loading in a training programme can be thought of as a ‘dose-response’ relationship, in other words you will get a response from your body depending on the dose (of exercise or loading) you do. The body grows in a relatively linear fashion from the age of two until children hit the pubertal growth spurt. Girls tend to undergo the pubertal growth spurt before boys (see figure 1). If your body is growing, it is already under load from the process of growth. Jumping, running and other sports can add more load onto the body, which can sometimes result in pain.

Peak Height Velocity (PHV) is the period when the growth spurt is happening Females achieve their PHV earlier than males (on average for females at approximately age 12, males age 14) but there is a wide range in age from when individuals will achieve their PHV, from 9.5 to 14.5 years in females and 10.5 to 16 years in males. This can result in different responses to the same ‘dose’ of external load applied to athletes. For example, if two children undergo the same training load but one child was at peak height velocity they may be more likely to sustain an injury or growth related pain compared to a child that was months or years away from their PHV.

Figure 1: Peak Height Velocity for American Girls and Boys

A prediction of how far an individual is from their Age of Peak Height Velocity (APHV) can be calculated from the athletes gender, date of birth, date of measurement, height, sitting height and weight, and is based on the differential growth and timing of leg length and sitting height.

The closer an individual is to APHV the more accurate the prediction. Ideally the age to make the most accurate prediction would be 9 to 13 years in females and 12 to 16 years in males. This calculation has been shown to be accurate for white Caucasian population measured during the ages described previously.

Ensuring the accuracy of the measurements is essential, as any errors (especially in sitting height) will dramatically alter the precision of the prediction.

Knowing the APHV for individual athletes means we can tailor the loading programme for that particular athlete, during the training season and hopefully reduce pain from over-training whilst training during APHV. This handy online calculator does the calculation for you: https://kinesiology.usask.ca/growthutility/phv_ui.php

Another source of information that is useful for those planning training sessions for adolescent athletes is the subjective assessment of the exertion required to do the sessions (the rate of perceived exertion). In other words, how difficult is the session to complete for each individual on a score from 0-20 where 0 is the easiest score and 20 is maximum possible effort. The RPE scale is used to measure the intensity of exercise. The RPE scale runs from 0 – 20. The numbers below relate to phrases used to rate how easy or an activity feels.

Figure 2: Borg Rate of Perceived Exertion Scale

| Level of exertion | ||

| 1 | ||

| 2 | ||

| 3 | ||

| 4 | ||

| 5 | ||

| 6 | No exertion at all | |

| 7 | Extremely light | |

| 8 | ||

| 9 | Very light | For a healthy person this would be walking at your own pace for a few minutes |

| 10 | ||

| 11 | Light | |

| 12 | ||

| 13 | Somewhat hard | Feels ‘somewhat hard’ but OK to continue |

| 14 | ||

| 15 | Hard (Heavy) | |

| 16 | ||

| 17 | Very hard | Healthly athletes can still go on but really has to push themselves, they feel heavy and very tired |

| 18 | ||

| 19 | Extremely hard | This is usually the most strenuous exercise athletes will experience |

| 20 | Maximal exertion |

Using the RPE gives us feedback on how athletes are feeling. The numbers should hopefully correlate with how hard the trainer expects the session to be. So if the trainer was planning a light session but the athletes were recording RPE of 16 and above, then the trainer may need to reconsider his training plan.

The negative effects of overloading can be injuries, pain, fatigue, burnout, and ultimately, reduced performance, the opposite to what we are trying to achieve by training. Sometimes the first indicator of overtraining is a higher average RPE than normal to a training session, which may indicate the athlete is overloaded and may need a longer rest period, or lighter sessions for a while.

So how can we reduce the negative effects of too much load?

- First we need to quantify the number of sessions we are doing per week. Start by making a training diary. Record all the organised training sessions – gym, track, other sports, PE at school etc. However, this does not take into account the unorganised loading that our bodies undertake, such as playing with friends, skateboarding, etc., but is a good start. (If you did include the unorganised load that would mean your calculations at the end would be more accurate).

- We can get a subjective reflection on the amount of load that athletes feel they are under by using consistent measures over a period of time such as RPE. Subjective measures such as rate of perceived exertion (RPE) are moderately reliable if we are looking at the same subject over a period of time. Reviewing their scores and what you expected the athletes to score is important when planning future sessions so you can load the athletes appropriately.

- Understanding when the athlete is likely to hit their APHV gives the person who is planning the loading programme, a time period where they may want to increase flexibility sessions and perhaps reduce the load during this time period for their athlete.

- Make sessions fun, enjoyable and tailor them as best you can to each individual athlete

- Be flexible, although it is frustrating to have planned a session and then have to change it at the last moment, we need to listen to our athletes and, if they are not prepared for the load, of the training session they may break down.

- Make sure you encourage rest days, particularly after heavy training days. Athletes need to be allowed to load and recover so they can positively adapt to the load.

Remember we are here to help you stay on the track, on the field and enjoying your sport in a healthy manner. Get in touch if you would like more information

Glossary of terms:

Loading

RPE : Rate of perceived exertion

PHVC: Peak Height Velocity Calculation – the approximate date the body will be growing through the fastest rate of growth.

APHV (Age of peak height velocity)

References:

Lambert, M.I., Borreson, J. (2010) Measuring training load in sports. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. Sep;5(3):406-11

IAAF specific considerations for the child and adolescent athlete https://www.iaaf.org/download/download?filename=538bb448-c750-452d-b01a-144b10a51aa6.pdf&urlslug=Chapter%204%3A%20Growth%20and%20Development

Mirwald, R.L., Baxter-Jones, A.D.G., Bailey, D.A., Beunen G.P. An assessment of maturity from anthropometric measurements. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise 2002: 34(4); 689-694

https://kinesiology.usask.ca/growthutility/phv_ui.php

Ross WD, Marfell-Jones MJ. Kinanthropometry. In MacDougall JD, Wenger HA, Green HJ, eds. Physiological Testing of the High-Performance Athlete, pp 223-308. Champaign, Illinois: Human Kinetics Books, 1